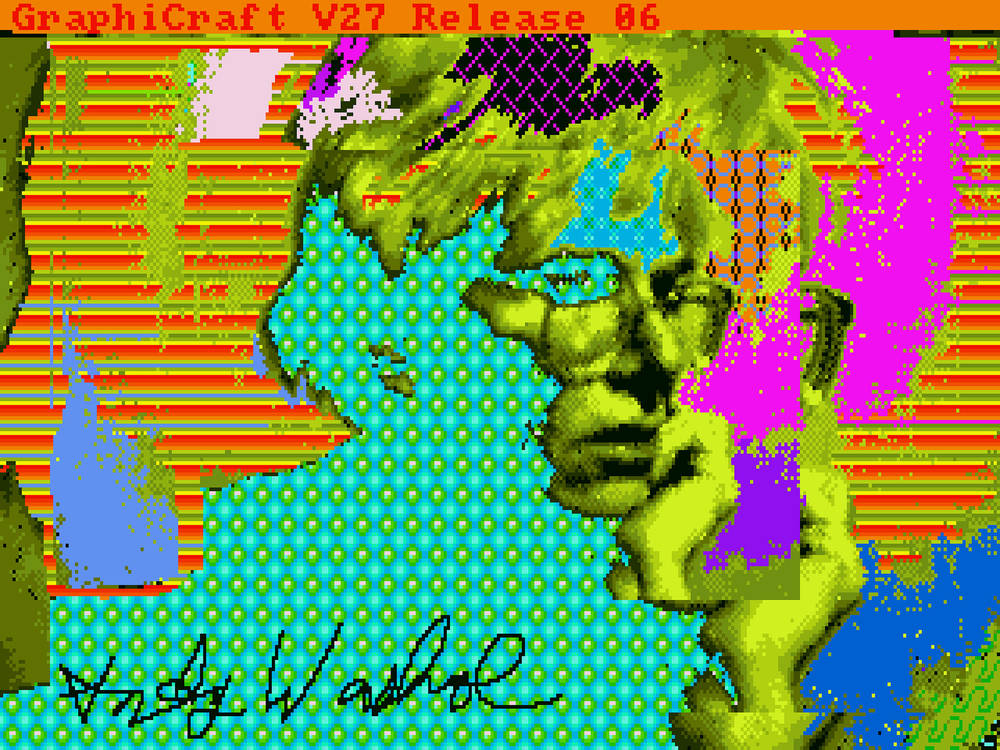

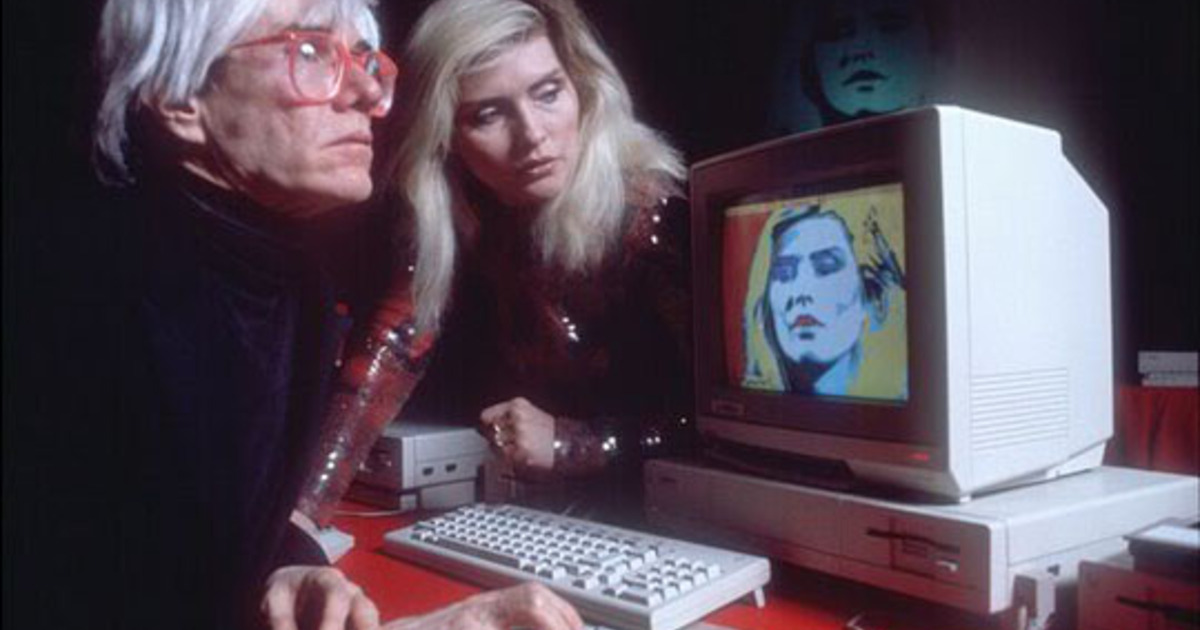

In 01985, Andy Warhol used an Amiga 1000 personal computer and the GraphiCraft software to create a series of digital works. Warhol’s early computer artworks are now viewable after 30 years of dormancy.

Commodore International commissioned Warhol to appear at the product launch and produce a few public pieces showing off the Amiga’s multimedia capabilities. According to the report, “Warhol’s presence was intended to convey the message that this was a highly sophisticated yet accessible machine that acted as a tool for creativity.”

In addition to creating a series of public pieces, Warhol made digital works on his own time. He was given a variety of pre-release hardware and software. This led him to eventually experiment with digital photography and videography, edit animation and compose digital audio pieces. The Studio for Creative Inquiry’s report states:

All of this (digital photography, video capturing, animation editing, and audio composition) had been done to limited extents earlier, but Warhol was an incredibly early adopter in this arena and may be the first major artist to explore many of these mediums of computer art. He almost certainly was the earliest (if not the only, given several pre-release statues) possessor of some of this hardware and software and, given their steep later sale prices, possibly the only person to have such a collection.

Decades later, artist Cory Arcangel learned of Warhol’s Amiga experiments from a YouTube clip showing Warhol at the launch altering a photo of Deborah Harry by using what nowadays would be considered basic digital art tools, such as flood fills. (shown in the above video). This scene set in motion what would become a 3-year-long quest of technological feats and multidisciplinary collaboration to recover and catalog the previously-unknown Warhol artworks living in degrading 30-year-old Amiga floppy disks.

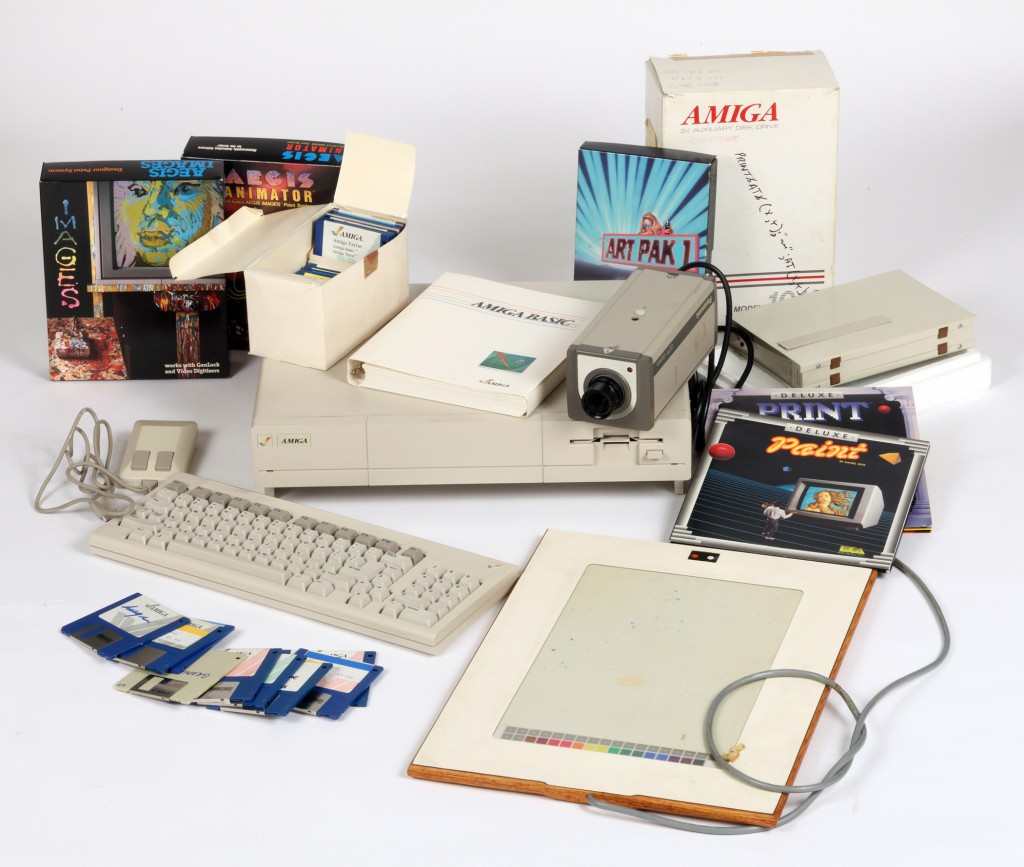

According to the contract with Commodore, Warhol owned the rights to any hardware given to him and all the work he created with the machines. After his death, his files and machines were stashed away and unpublished in the archives at the Warhol Museum. The collection contained two Amiga 1000 computers, one of which was never used, parts of a video capturing hardware setup, a drawing tablet, and an assortment of floppy disks of mostly commercial software in their original boxes:

It was immediately clear that this was an exciting window into history given that several pieces of Amiga hardware had shipping labels directly from Commodore, others had internal Commodore labels warning that the components were not yet for sale lacking FCC approval, and that the drawing tablet appeared hand-made.

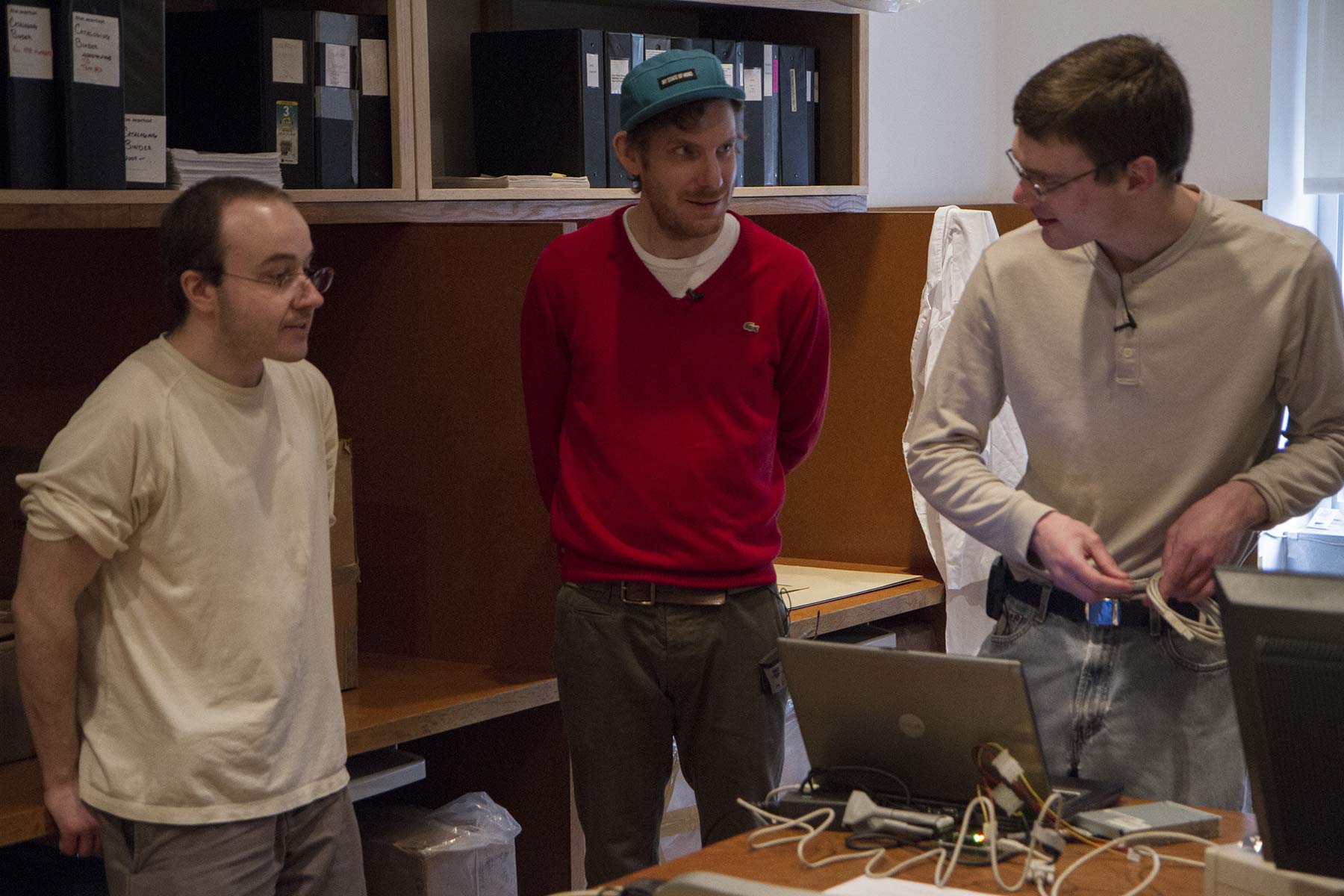

In December 02011, Arcangel approached the Warhol Museum with the proposal of restoring the Amiga hardware and archive the contents of associated disks. In April 02012, he teamed up with the Carnegie Mellon Computer Club, a team of experts in obsolete computer maintenance and software preservation, to retrocompute and forensically extract data from the roughly 40 Amiga disks. 10 of those disks were found to contain a total of at least 13 graphic files they think to be created or altered by Warhol.

Cory Arcangel (Center), and CMU Computer Club members Michael Dille (Left), Keith A. Bare (Right) during the data recovery process at The Andy Warhol Museum. Photo: Hillman Photography Initiative, CMOA.

With a lot of hacking, sleuthing and extensive Amiga knowledge, the CMU Computer Club figured out how to examine the contents on Warhol’s disks. In a simplified explanation, it boils down to a two-tier process–first creating copies of the disks in a standard filesystem-level disk image and then looking through those files to see if any were in known graphic formats. Some were, some weren’t. It took months of retrocomputing the GraphiCraft software to convert the unknown graphic formats into a file that could be opened today.

To extract data and generate an archival dump, the Computer Club used a USB device called KryoFlux. This device attaches a floppy drive to the modern day PC and reads and writes standard-format floppy disks. But its real advantage is its ability to capture a very low-level picture of the disks. The KryoFlux created raw dumps as close as possible to the original floppies and standard filesystem disk images (ADF files). These ADF files work with Amiga emulators. Using the KryoFlux also allowed for better handling of degrading and fragile disks (many had magnetic materials coming off the substrate) and it generated standard ADF files for floppy disks containing non-standard encodings or copy-protection schemes.

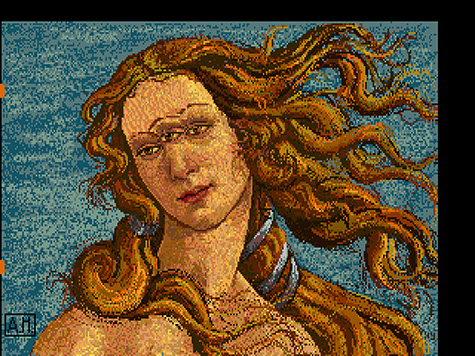

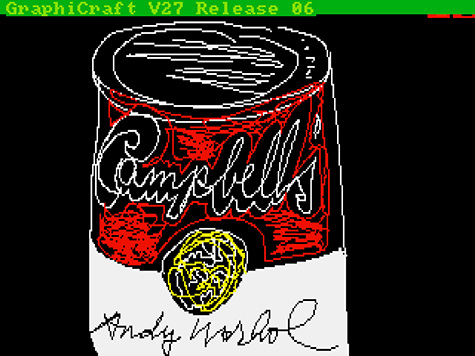

The following day after making copies of Warhol’s disks, the disk images were loaded in the Amiga emulator in the basement of CMU Computer Club member Michael Dille. The disk hand-labeled “GraphiCraft” contained files with names like “flower.pic,” “campbells.pic” and “marilyn1.pic,” a clear sign that something was on that disk. The .pic files were unrecognizable by modern software and would later require the club’s resident Amiga expert Keith Bare to do deeper hacking and reverse computer engineering in order to crack the GraphiCraft format. But on that day, two files on the same disk named “tut” and “venus” were in a common format used on Amigas, “Interchange File Format” (IFF). These two files were readable by using the software ImageMagick to convert the .iff files to PNG–a format modern software can understand. On the evening of March 2, 02013, Warhol’s Venus displayed on the screen for the first time in 30 years.

Warhol’s digital works are proof that the Amiga 1000 was highly impressive for its time. The first of the Amigas, it already had better sound and graphics abilities than its competitors. It had a 4-channel stereo and up to 4,096 colors and 640×200 pixels. In comparison, PCs had “beepers” and up to 16 colors, while Macintoshes had 22.5kHz mono audio and monochrome displays (Studio for Creative Inquiry’s report).

These recovered images give insight to the workflow and capabilities of early computer art. In the above photo, Warhol used clip art to create the three identical eyes on Venus. The digital reinterpretation of Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup, pictured below, was modified with a line tool. It shows Warhol’s willingness to experiment and adapt to a new medium.

Earlier this week, the Carnegie Museum of Art released Trapped, the second of a five-part documentary series by the Hillman Photography Initiative to “investigate the world of images that are guarded, stashed away, barely recognizable or simply forgotten.” The short documentary gives a detailed look at the techno-archaeologists’ process of decoding the obsolete file types. (Minute 8:47 shows the copying of Warhol’s disks.)

The forensic effort and process of studying the disks contents sheds light to the impermanent nature of digital material and the need for digital preservation. “In a way, a lot of the data and things we work with almost seem like it’s imaginary,” explained Bare in Trapped, “It’s electrons in a machine. You can turn it into photons if you use a display, but in some sense it’s almost like it’s not even there.”