Brian Eno’s creative activities defy categorization. Widely known as a musician and producer, Eno has expanded the frontiers of audio and visual art for decades, and posited new ways of approaching creativity in general. He is a thinker and speaker, activist and eccentric. He formulated the idea of the Big Here and Long Now—a central conceptual underpinning of The Long Now Foundation, which he helped found with Stewart Brand and Danny Hillis in 01996. Eno’s artistic career has often dealt closely with concepts of time, scale, and, as he puts it in the liner notes to Apollo, “expanding the vocabulary of human feeling.”

Ambient and Generative Art

Brian Eno coined the term ‘ambient music’ to describe a kind of music meant to influence an ambience without necessarily demanding the listener’s full attention. The notes accompanying his 01978 album Ambient 1: Music for Airports differentiate it from the commercial music produced specifically for background listening by companies such as Muzak, Inc. in the mid-01900s. Eno explains that ambient music should enhance — not blanket — an environment’s acoustic and atmospheric characteristics, to calming and thought-inducing effect. It has to accommodate various levels of listening engagement, and therefore “must be as ignorable as it is interesting” (Eno 296).

Ambient music can have a timeless quality to it. The absence of a traditional structure of musical development withholds a clear beginning or end or middle, tapping into a sense of deeper, slower processes. It lets you “settle into time a little bit,” as Eno said in the first of Long Now’s SALT talks. As TimeMagazine writes, “the theme of time, foreshortened or elongated, is a defining feature of Eno’s musical and visual adventures. But it takes a long lens, pointing back, to bring into focus the ways in which his influence has seeped into the mainstream.”

Eno’s use of the term ‘ambient’ was, however, a product of a long process of musical development. He had been thinking specifically about this kind of music for several years already, and the influence of minimalist artists such as Terry Riley, Steve Reich and Philip Glass had long shaped his musical ideas and techniques. He also drew on many other genres, including Krautrockbands such as Tangerine Dream and Can, whose music was contemporaneous and influential in Eno’s early collaborations with Robert Fripp, e.g. (No Pussyfooting). While their music might not necessarily fall into the genre ‘ambient,’ David Sheppard notes that “Eno and Fripp’s lengthy essays shared with Krautrock a disavowal of verse/chorus orthodoxy and instead relied on an essentially static musical core with only gradual internal harmonic developments” (142). In his autobiography, Eno also points to developments in audio technology as key in the development of the genre, as well as one particularly insightful experience he had while bedridden after an accident:

New sound-shaping and space-making devices appeared on the market weekly (and still do), synthesizers made their clumsy but crucial debut, and people like me just sat at home night after night fiddling around with all this stuff, amazed at what was now possible, immersed in the new sonic worlds we could create.

And immersion was really the point: we were making music to swim in, to float in, to get lost inside.

This became clear to me when I was confined to bed, immobilized by an accident in early 01975. My friend Judy Nylon had visited, and brought with her a record of 17th-century harp music. I asked her to put it on as she left, which she did, but it wasn’t until she’d gone that I realized that the hi-fi was much too quiet and one of the speakers had given up anyway. It was raining hard outside, and I could hardly hear the music above the rain — just the loudest notes, like little crystals, sonic icebergs rising out of the storm. I couldn’t get up and change it, so I just lay there waiting for my next visitor to come and sort it out, and gradually I was seduced by this listening experience. I realized that this was what I wanted music to be — a place, a feeling, an all-around tint to my sonic environment.

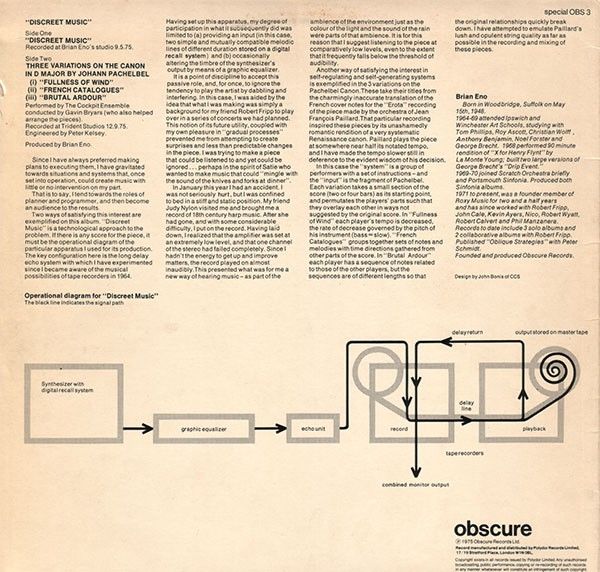

It was not long after this realization that Eno released the album Discreet Music, which he considers to be an ambient work, mentioning a conceptual likeness to Erik Satie’s Furniture Music. One of the premises behind its creation was that it would be background for Robert Fripp to play over in concerts, and the title track is about half an hour long — as much time as was available to Eno on one side of a record.

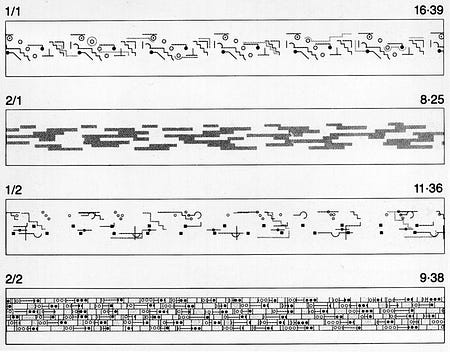

It is also an early example in his discography of what later became another genre closely associated with Eno and with ambient: generative music. In the liner notes — which include the story of the broken speaker epiphany — he writes:

Since I have always preferred making plans to executing them, I have gravitated towards situations and systems that, once set into operation, could create music with little or no intervention on my part.

That is to say, I tend towards the roles of planner and programmer, and then become an audience to the results.

This notion of creating a system that generates an output is an idea that artists had considered previously. In fact, in the 18th century even Mozart and others experimented with a ‘musical dice game’ in which the numerical results of rolling dice ‘generated’ a song. More relevant to Brian Eno’s use of generative systems, however, was the influence of 20th century composers such as John Cage. David Sheppard’s biography of Brian Eno describes how Tom Phillips — a teacher at Ipswich School of Art where Eno studied painting in the mid 01960s — introduced him to the musical avant garde scene with the works of Cage, Cornelius Cardew, and the previously mentioned minimalists Reich, Glass and Riley (Sheppard 35–41). These and other artists exposed Eno to ideas such as aleatory and minimalist music, tape experimentation, and performance or process-based musical concepts.

Eno notes Steve Reich’s influence on his generative music, acknowledging that “indeed a lot of my interest was directly inspired by Steve Reich’s sixties tape pieces such as Come Out) and It’s Gonna Rain” (Eno 332). And looking back on a 01970 performance by the Philip Glass Ensemble at the Royal College of Art, Brian Eno highlights its impact on him:

This was one of the most extraordinary musical experiences of my life — sound made completely physical and as dense as concrete by sheer volume and repetition. For me it was like a viscous bath of pure, thick energy. Though he was at that time described as a minimalist, this was actually one of the most detailed musics I’d ever heard. It was all intricacy and exotic harmonics. (Sheppard 63–64)

The relationship between minimalism and intricacy, in a sense, is what underlies the concept of generative music. The artist designs a system with inputs which, when compared to the plethora of outputs, appear quite simple. Steve Reich’s It’s Gonna Rain is, in fact, simply a single 1.8 second recording of a preacher shouting “It’s gonna rain!” played simultaneously on two tape recorders. Due to the inconsistencies in the two devices’ hardware, however, the recordings play at slightly different speeds, producing over 17 minutes of phasing in which the relationship between the two recordings constantly changes.

Brian Eno has taken this capacity for generative music to create complexity out of simplicity much further. Discreet Music (01975) used a similar approach, but started with recordings of different lengths, used an echo system, and altered timbre over time. The sonic possibilities opened by adding just a few more variables are vast.

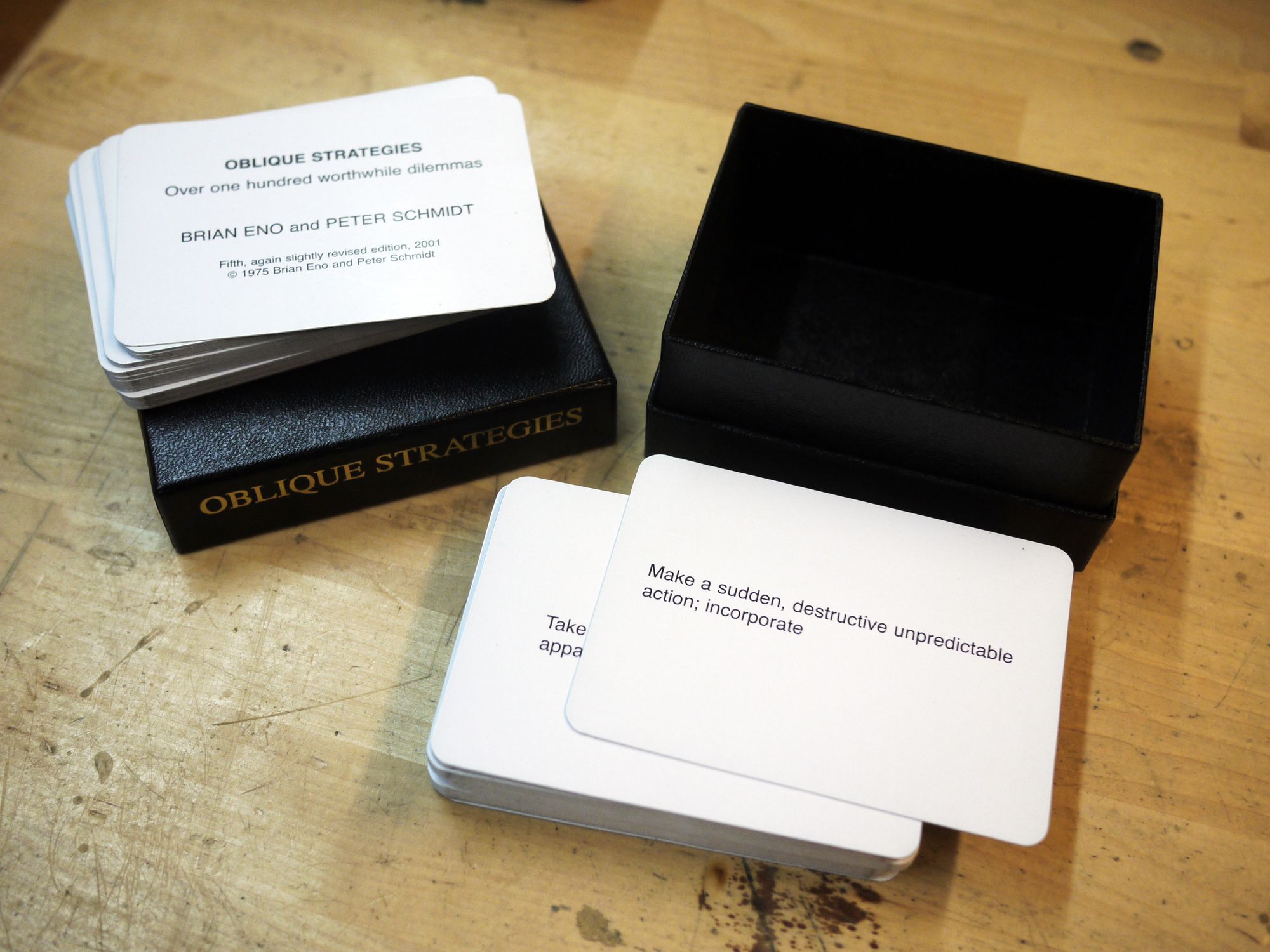

This experimental approach to creativity is just one of many that Eno explored, including some non-musical means of prompting unexpected outputs. The same year that Discreet Music was released, he collaborated with painter Peter Schmidt to produce Oblique Strategies: Over One Hundred Worthwhile Dilemmas.

The work is a set of cards, each one with an aphorism designed to help people think differently or to approach a problem from a different angle. These include phrases such as “Honour thy error as a hidden intention,” “Work at a different speed,” and “Use an old idea.” Schmidt had created something a few years earlier along the same lines that he called ‘Thoughts Behind the Thoughts.’ There was also inspiration to be drawn from John Cage’s use of the I Ching to direct his musical compositions and George Brecht’s 01963 Water Yam Box. Like a generative system, the Oblique Strategies provides a guiding rule or principle that is specific enough to focus creativity but general enough to yield an unknown outcome, dependent on a multitude of variables interacting within the framework of the strategy.

Three decades later, generative systems remained a central inspiration for Eno and a source of interesting cross-disciplinary collaboration. In 02006, he discussed them with Will Wright, creator of popular video game series The Sims, at a Long Now SALT talk:

Wright observed that science is all about compressing reality to minimal rule sets, but generative creation goes the opposite direction. You look for a combination of the fewest rules that can generate a whole complex world that will always surprise you, yet within a framework that stays recognizable. “It’s not engineering and design,” he said, “so much as it is gardening. You plant seeds. Richard Dawkins says that a willow seed has only about 800K of data in it.” — Stewart Brand

Brian Eno has always been interested in this explosion of possibilities, and has in recent years created generative art that incorporates both audio and visuals. He notes that his work 77 Million Paintings would take about 10,000 years to run through all of its possibilities — at its slowest setting. Long Now produced the North American premiere of 77 Million Paintings at Yerba Buena center for the Arts in 02007, and members were treated to a surprise visit from Mr. Eno who spoke about his work and Long Now.

Eno also designed an art installation for The Interval, Long Now’s cafe-bar-museum venue in San Francisco. “Ambient Painting #1” is the only example of Brian’s generative light work in America, and the only ambient painting of his that is currently on permanent public display anywhere.

Another generative work called Bloom, created with Peter Chilvers, is available as an app.

Part instrument, part composition and part artwork, Bloom’s innovative controls allow anyone to create elaborate patterns and unique melodies by simply tapping the screen. A generative music player takes over when Bloom is left idle, creating an infinite selection of compositions and their accompanying visualisations. — Generativemusic.com

Eno’s interest in time and scale (among other things) was shared by Long Now co-founder Stewart Brand, and they were in close correspondence in the years leading up to the creation of The Long Now Foundation. Eno’s 01995 diary, published in part in his autobiography, describes that correspondence in its introduction:

My conversation with Stewart Brand is primarily a written one — in the form of e-mail that I routinely save, and which in 1995 alone came to about 100,000 words. Often I discuss things with him in much greater detail than I would write about them for my own benefit in the diary, and occasionally I’ve excerpted from that correspondence. — Eno, ix

Out of Eno’s involvement with the establishment of The Long Now Foundation emerged in his essay “The Big Here and Long Now”, which describes his experiences with small-scale perspectives and the need for larger ones, as well as the artist’s role in social change.

This imaginative process can be seeded and nurtured by artists and designers, for, since the beginning of the 20th century, artists have been moving away from an idea of art as something finished, perfect, definitive and unchanging towards a view of artworks as processes or the seeds for processes — things that exist and change in time, things that are never finished. Sometimes this is quite explicit — as in Walter de Maria’s “Lightning Field,” a huge grid of metal poles designed to attract lightning. Many musical compositions don’t have one form, but change unrepeatingly over time — many of my own pieces and Jem Finer’s Artangel installation “LongPlayer” are like this. Artworks in general are increasingly regarded as seeds — seeds for processes that need a viewer’s (or a whole culture’s) active mind in which to develop. Increasingly working with time, culture-makers see themselves as people who start things, not finish them.

And what is possible in art becomes thinkable in life. We become our new selves first in simulacrum, through style and fashion and art, our deliberate immersions in virtual worlds. Through them we sense what it would be like to be another kind of person with other kinds of values. We rehearse new feelings and sensitivities. We imagine other ways of thinking about our world and its future.

[…] In this, the 21st century, we may need icons more than ever before. Our conversation about time and the future must necessarily be global, so it needs to be inspired and consolidated by images that can transcend language and geography. As artists and culture-makers begin making time, change and continuity their subject-matter, they will legitimise and make emotionally attractive a new and important conversation.

The Chime Generator and January 07003

Brian Eno’s involvement with Long Now began through his discussions with Stewart Brand about time and long-term thinking, and the need for a carefully crafted sonic experience to help The Clock evoke deep time for its visitors posed a challenge Eno was uniquely suited to take on.

From its earliest conception, the imagined visit to the 10,000-Year Clock has had aural experience at its core. One of Danny Hillis’ earliest refrains about The Clock evokes this:

It ticks once a year, bongs once a century, and the cuckoo comes out every millennium. —Danny Hillis

In the years of brainstorming and design that have molded this vision into a tangible object, a much more detailed and complicated picture has come into focus, but sound has remained central; one of the largest components of the 10,000-Year Clock will be its Chime Generator.

Rather than a bong per century, visitors to the Clock will have the opportunity to hear it chime 10 bells in a unique sequence each day at noon. The story of how this came to be is told by Mr. Eno himself in the liner notes of January 07003: Bell Studies for The Clock of the Long Now, a collection of musical experiments he synthesized and recorded in 02003:

When we started thinking about The Clock of the Long Now, we naturally wondered what kind of sound it could make to announce the passage of time. Bells have stood the test of time in their relationship to clocks, and the technology of making them is highly evolved and still evolving. I began reading about bells, discovering the physics of their sounds, and became interested in thinking about what other sorts of bells might exist. My speculations quickly took me out of the bounds of current physical and material possibilities, but I considered some license allowable since the project was conceived in a time scale of thousands of years, and I might therefore imagine bells with quite different physical properties from those we now know (Eno 3).

Bells have a long history of marking time, so their inclusion in The Clock is a natural fit. Throughout this long history, they’ve also commonly been used in churches, meditation halls and yoga studios to offer a resonant ambiance in which to contemplate a connection to something bigger, much as The Clock’s vibrations will help inspire an awareness of one’s place in deep time. Furthermore, bells were central to some early forms of generative music. While learning about their history, Eno found a vast literature on the ways bells had been used in Britain to explore the combinatorial possibilities afforded by following a few simple rules:

Stated briefly, change-ringing is the art (or, to many practitioners, the science) of ringing a given number of bells such that all possible sequences are used without any being repeated. The mathematics of this idea are fairly simple: n bells will yield n! sequences or changes. The ! is not an expression of surprise but the sign for a factorial: a direction to multiply the number by all those lower than it. So 3 bells will yield 3 x 2 x 1 = 6 changes, while 4 bells will yield 4 x 3 x 2 x 1 = 24 changes. The ! process does become rather surprising as you continue it for higher values of n: 5! = 120, and 6! = 720 — and you watch the number of changes increasing dramatically with the number of bells. — Eno 4

Eno noticed that 10 bells in this context will provide 3,628,800 sequences. Ring one of those each day and you’ll be occupied for almost exactly 10,000 years, the proposed lifespan of The Clock.

Following this line of thinking, he imagined using the patterns played by the bells as a method of encoding the amount of time that had elapsed since The Clock had started ringing them. Writing in 02003, he says:

I wanted to hear the bells of the month of January, 07003 — approximately halfway through the life of the Clock.

I had no idea how to generate this series, but I had a good idea who would.

I wrote to Danny Hillis asking whether he could come up with an algorithm for the job. Yes, he wrote back, and in fact he could come up with an algorithm for generating all the possible algorithms for that job. Not having the storage space for a lot of extra algorithms in my studio, I decided to settle for just the one. — Eno 6

And so, the pattern The Clock’s bells will ring was set. Using a start point (02003 in this case), one can extrapolate the order in which the Bells will ring for a given day in the future. The title track of the album features the synthesized bells played in each of the 31 sequences for the month of January in the year 07003. Other tracks on the album use different algorithms or different bells to explore alternative possibilities; taken together, the album is distinctly “ambient” in Eno’s tradition, but also unique within his work for its minimalism and procedurality.

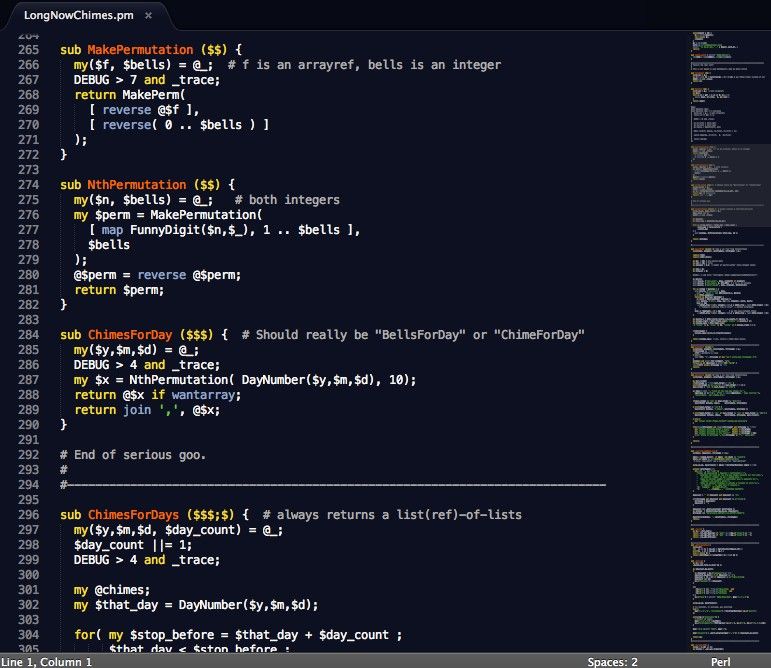

The procedures guiding the composition are strict enough that they can be written in computer code. A Long Now Member named Sean Burke was kind enough to create a webpage that illustrates how this works. The site allows visitors to enter a future date and receive a MIDI file of the chimes from that day. You can also download the algorithm itself in the form of a Perl script or just grab the MIDI data for all 10,000 years and synthesize your own bells.

If the bell ringing algorithm is a seed, in what soil can it be planted and expected to live its full life? Compact disks, Perl scripts and MIDI files have their uses, of course, but The Clock has to really last in a physical, functional sense for many thousands of years. To serve this purpose, the Chime Generator manifests the algorithm in stainless steel Geneva wheels rotating on bearings of silicon nitride.

One of the first prototypes for this mechanism resides at The Interval. In its operation, one can see that the Geneva wheels rotate at different intervals because of their varying numbers of slots. Together, the Geneva wheels represent the ringing algorithm and sequentially engage the hammers in all 3.6 million permutations. For this prototype, the hammers strike Tibetan Bowl Gongs to sound the notes, but any type of bell can be used.

The full scale Chime Generator will be vertically suspended in the Clock shaft within the mountain. The Geneva wheels will be about 8 feet in diameter, with the full mechanism standing over seventy feet in height.

The bells for the full scale Chime Generator won’t be Tibetan Bowl Gongs like in the smaller prototype above. Though testing has been done within the Clock chamber to find its resonant frequency, the exact tuning and design of the Clock’s bells will be left until the chamber is finished and most of the Clock is installed in order to maximize their ability to resonate within the space.

Like much of Brian Eno’s work, the chimes in the 10,000-Year Clock draw together far-flung traditions, high and low tech, and science and art to create a meditative experience, unique in a given moment, but expansive in scale and scope. They encourage the listener to live and to be present in the moment, the “now,” but to feel that moment expanding forward and backward through time, literally to experience the “Long Now.”

Written by Austin Brown and Alex Mensing. Edited and updated by Ahmed Kabil.

Works Cited & Where to Learn More

Autobiography

Biography

Talks

- Talk on Generative Music for In Motion Magazine. June 01996.

- “The Long Now,” Long Now SALT talk, November 02003.

- “Playing With Time,” Long Now SALT talk with Will Wright, June 02006.

- Brian Eno speaks in Moscow, 02011. via Austin Kleon.

- “The Long Now, Now”, Long Now SALT talk, January 02014.

Articles

- “The Big Here and Long Now” by Brian Eno for The Long Now Foundation. 01996.

- “Light Years into the Future” by Michael Brunton for Time Magazine. November 02006.

- “New Eno Music Gets ‘Generative’” by Noah Shachtman for Wired. October 02001.

- New Yorker article on Long Now board member David Eagleman, including an experiment with Brian Eno on time & rhythm perception

- 01979 interview with Brian Eno by Lester Bangs

- History and description of generative music, excerpted from dissertation by Norbert Herber.

- “Brian Eno designs Sound and Light Art for The Interval at Long Now” by mikl em for Long Now blog. July 16, 02013.

This is the first of a series of articles, “Music, Time and Long-Term Thinking,” in which we will discuss music and musicians who have engaged various aspects of long-term thinking, both historically and in the contemporary scene.