In the effort to understand our environment, scientists generally rely on natural observations to describe the earth’s past. They examine tree rings, oxygen isotopes, sedimentary rock, pollen, and many other physical records from which we can glean information. These methods are quite fruitful, and when combined they offer compelling evidence. But wouldn’t it be nice if, at least for the last few millennia, our ancestors had just recorded all of that information for us?

Occasionally they did, particularly when they encountered conditions or events that they considered extremely important. For example, swarms of locusts that ate all of their food. Conservation Magazine describes a project by a team of scientists in China who have compiled over 8,000 historical documents that chronicle the insect’s effects:

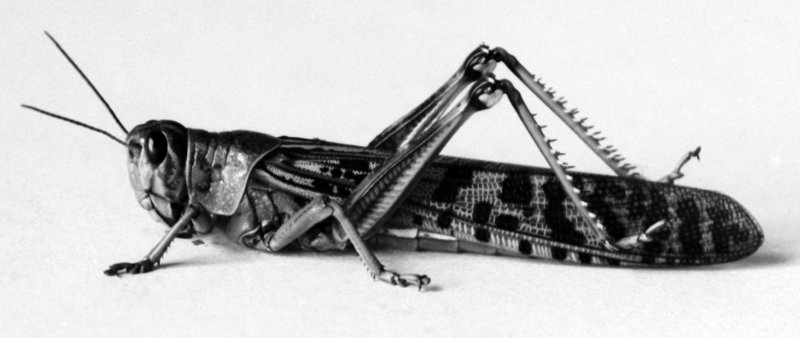

“Outbreak of Oriental migratory locusts (Locusta migratoria manilensis) was, together with drought and flood, considered one of the three most severe natural disasters causing damage to crop production in ancient China,” a team led by Huidong Tian of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing notes in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. “The earliest known written record of locusts was found inscribed on an ox bone in Oracle Script (Jiaguwen, the earliest Chinese script) 3,500 years ago, asking: ‘Will locusts appear in the field; will it not rain?’” Ever since, local histories and government documents have been littered with detailed records of locust outbreaks.

The study has shown a link between dry conditions and locust outbreaks, providing a rare biological source of evidence for climate variations. Regardless of whether or not the authors of these documents intended for them to be useful to future generations, their efforts to describe and catalog their environment in an enduring medium have proven very valuable to us, thousands of years later.