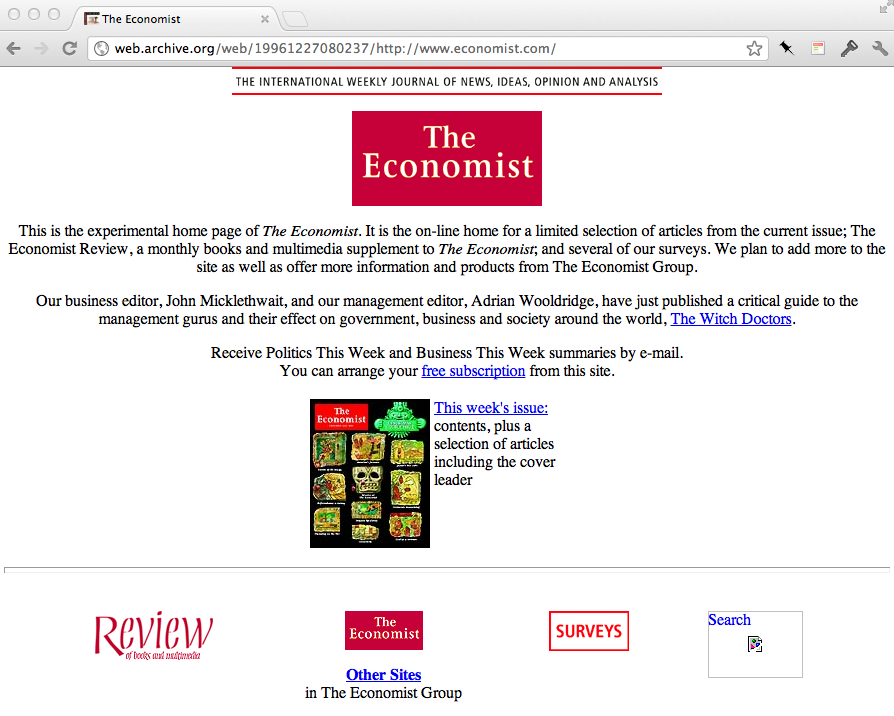

In 01994, The Economist first launched its very own website. Before long, America Online pronounced it one of the world’s best news sites, and numerous readers depended on it for their updates on current events.

Yet 18 years later, this once valued page is nowhere to be found. (The Wayback Machine’s records only go back to the end of 1996.) Long forgotten, it died a quiet death on a buried floppy disk somewhere, while the world, and The Economist, moved on to bigger and better internet capabilities.

How sad, The Economist’s Babbage blog writes, that we’ve lost so much of this early internet content. And how dangerous, as well. The threat of a digital dark age doesn’t just lurk in the ever-increasing pace of technological innovation, and its growing waste pile of obsolete software platforms. Perhaps even more acutely, it looms also in our own lack of awareness. Amidst the sheer volume of data that we swim through on the internet these days, we simply have no room or time to think about everything we’ve lost. Babbage writes:

The explosive growth of internet services such as e-mail, music downloads, video streaming, internet television, and, above all, the web itself, with its multitude of applications, has overwhelmed the digital world’s capacity to reflect upon what has passed before.

This deluge of data and applications has drowned out our “right to remember,” the author writes. Driven toward each day’s new buffet of information and possibilities, we simply have no time to look back. It’s all we can do to swallow our losses and keep on swimming. Babbage quotes both Stewart Brand and Danny Hillis in calling attention to the consequences of such a collective loss of memory:

There has been so little time to remember, let alone record, the past for posterity. Rapid turnover of information has made total loss the norm. It has been simply a matter of delete, clean the hard-drives and prepare for tomorrow’s deluge. “Civilization is developing severe amnesia as a result,” says Stewart Brand of the Long Now Foundation. Danny Hillis, a pioneer of parallel computing and machine intelligence, fears the world has become stuck in a digital dark age, with few cultural artifacts from its digital past to point the way.

Babbage sees a hopeful solution in organizations and people who engage in digital preservation efforts – such as Brewster Kahle, whose Wayback Machine documents the history of web pages, and whose Internet Archive is creating a library of everything ever posted to the web. But the ultimate key to counteracting our collective amnesia, the article suggests, is the availability of open source archives: collections that not only preserve information, but also make it accessible to the public.

… without paper libraries, people would find it hard to exercise their “right to remember.” That means, for example, journalists would find it difficult to hold politicians accountable for what they had promised. Historians would have trouble holding a mirror up to a society to show its vulnerabilities as well as its strengths. As much of public information is moving from printed to digital form, it is vital that virtual libraries archive as much of these digital media as they can for future reference and accountability.

Hopefully, the public availability of information will remind us how important it is to remember – and to be, collectively, accountable to future generations.