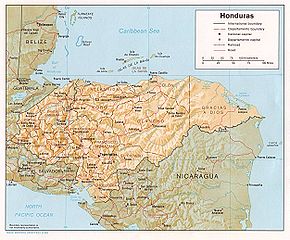

In 02011, economist Paul Romer was given an opportunity that few of his colleagues ever get: a chance to see one of his theories tested in a real-world setting. Octavio Sanchez, an idealistic government official in Honduras, saw in Romer’s proposal a resemblance to an idea of his own: to solve the country’s vexing problems by creating a semi-autonomous charter city in which a new and functional social order could be built “from scratch.”

Sanchez and Romer partnered up in what seemed to be a promising opportunity to put Honduras on a path to socio-economic development. But just a year later, their idealistic project seems to have fallen irreparably apart. Two NPR reporters recently traveled to Honduras to investigate what might have gone wrong.

As Romer explained in a 02009 SALT seminar and later in a TED talk, developing countries like Honduras are stuck in a vicious cycle of “bad rules.” Figuring out where to start the process of fixing these rules can be difficult. As Jacob Goldstein of NPR’s Planet Money explains,

“Say you want to start with the education system. The education system is terrible because teachers are always on strike. Teachers are always on strike because they don’t get paid. They don’t get paid because the government does a terrible job collecting taxes. Oh, and also, because the government doesn’t collect taxes, it can’t hire a proper police force. And there’s a huge backlog in the courts. And Hondurans think their cops, and for that matter lots of other government workers, can be bought and sold. So you have corruption, and chaos, and violence. How can you fix this? Where do you start?” (This American Life)

Rather than try to tackle all of these problems at once, both Romer and Sanchez concluded that the most effective solution would be to simply wipe the slate clean, and start from scratch in one little corner of the country. If successful, the new system could then be replicated on a larger scale. Planet Money’s Chana Joffe-Walt elaborates:

“Pick a totally uninhabited site, and … say, we’re going to create another alternative. And the city you build on this uninhabited site, Paul [Romer] calls it a charter city. The idea is, this city has its own set of laws. Its own cops, its own courts, its own schools, everything. This is a city where you start from scratch. And to make sure that the cops and courts and schools in this new city are good ones, you have to get help from rich countries. So, say you get the UK to let court cases in the charter city be appealed to courts in the UK. Maybe Canada sends in some Mounties. Now, Paul says, you have a place that works, right inside a poor country that doesn’t.”

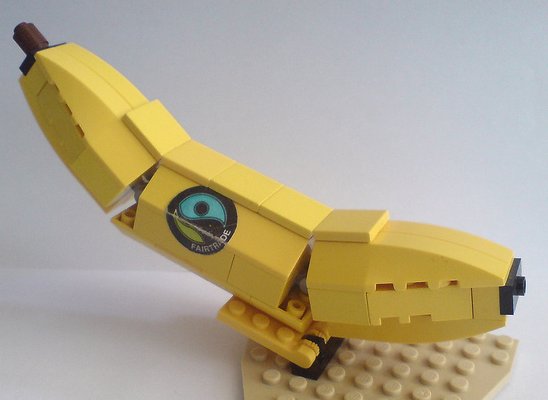

Sanchez and Romer were essentially proposing what mathematician Samuel Arbesman has recently called “procedural city generation.” Writing about the trend of constructing micro-cities with LEGO bricks, Arbesman explains that real cities derive their vibrant and organic “city feel” from what is known in mathematics as path dependence,

“where one’s current state is highly dependent on where one came from, and the decisions one has made along the way. Essentially, the state of the system is dependent on its path through the space of possible states.”

When starting from scratch, this city feel can be created by relying instead on a pre-determined set of rules, procedures, or algorithms – in other words, a charter.

But what makes Romer’s charter unique – and slightly more complicated than its LEGO equivalent – is its reliance on international guarantors; on the guidance of developed nations. It has prompted fellow economists to accuse Romer’s plan of neo-colonialism. Yet Romer insists that his proposal is different. Essential to the success of a charter city, he claims, is the notion of choice. A country must freely choose to invite foreign investors into a joint venture of city-building, and individuals must freely choose to join the new community and abide by its charter. Without coercion, Romer states, one cannot speak of colonialism.

Hondurans, however, disagreed. They felt belittled, turned into guinea pigs for a project construed by the international media as a North American scholar’s brilliant solution to the problem of poverty. Sanchez and his team responded first by reducing Romer’s involvement in the project; then by calling a stop to it altogether.

In a recent episode of This American Life, the Planet Money team asks: was this simply a petty disagreement over who should get credit for this plan?

In determining how to answer this question, the reporters remind listeners that

“… the phrase ‘Banana Republic’ was invented to describe Honduras. US-based fruit companies were hugely powerful here for a big chunk of the twentieth century. At one point, one company even funded a coup to overthrow the government. Before that, there were hundreds of years of Spanish colonialism.”

Unlike a LEGO micro city, a geographical region – no matter how uninhabited or desolate – always has history. It simply isn’t possible to escape path dependence and “start from scratch.” The history of Honduras is rife with painful periods of imperialism and exploitation – and the way in which the charter city project unfolded

Unlike a LEGO micro city, a geographical region – no matter how uninhabited or desolate – always has history. It simply isn’t possible to escape path dependence and “start from scratch.” The history of Honduras is rife with painful periods of imperialism and exploitation – and the way in which the charter city project unfolded

“… sent a clear message to Honduras: North Americans, the whole rich world, they don’t think you’re up to running your own country. So all this petty stuff is just not petty in Honduras. It really matters when a story in [the Economist] says that a Honduran idea is actually a brilliant plan imposed by a North American economist.”

But the legacy of colonialism does more than render Hondurans sensitive to new American efforts to get involved with the country’s development. Its current problems are in many ways the direct result of these episodes of imperialism. As Octavio Sanchez explains,

“We are poor not because we are dumb. We are poor because of our institutional arrangement, not because we lack the capacity to imagine things.”

It is worth asking, then, how much choice a country like Honduras really has in asking developed countries for help in combating poverty and corruption.

In sum, the story of how this project failed is not so much an illustration of how petty misunderstandings can ruin an idealistic project, but rather a lesson in the importance of looking back when you’re thinking about the long-term future, and acknowledging the ways in which your path through history will shape the course of your future.