Time is evoked in music in countless ways. In the first article in this series, we explored some of the long-term themes in Brian Eno’s work and traced that influence to his involvement with the 10,000-Year Clock. Through generative music — a compositional technique that uses a small set of rules to generate many unique outcomes — Eno created expansive compositions theoretically capable of lasting over extremely long periods of time. This is precisely the logic behind the 10,000-Year Clock’s Chime Generator.

Questions arise, however, when the extreme potential duration of combinatorially-generated music is taken as a challenge. How does one actually perform a piece that is 1,000 years long? Let’s explore two attempts to answer this question.

John Cage and As Slow As Possible

John Cage’s name will likely remain one of the most enduring among 20th century composers. He pioneered avant garde expeditions that pushed the boundaries of what could be considered composition. His experiments began after studying under another of the 20th century’s masters, the Austrian Arnold Schoenberg, himself a pioneer. One of Schoenberg’s major contributions to modern music was a style of composition he began to develop in the first decade of the 01900s. Though he rejected the term, it came to be known as atonality — lacking a tonal center, or key. Rejecting the key did away with the central organizing structure around which the vast majority of music was traditionally written. Tonal music was organized around a hierarchy of tones, with the key tone at the top. Atonality gave the composer the opportunity to throw out hierarchy and focus on any and all tones as he or she chose.

As Schoenberg and others further developed atonality, some received it well and others did not. Among those who did not were the newly ascendant Nazi party, labeling it “degenerate” and “Bolshevik.” In 01933, Schoenberg emigrated to the United States, where he would soon come to teach at UCLA. One of his students during this time was John Cage, who had explored compositional techniques similar to Schoenberg’s.

A particular avenue of Schoenberg’s that Cage followed is the expansion of the composer’s palette. Cage struggled with harmony, but his work broke down traditional definitions of how to compose and what could be considered an instrument, especially beginning the latter part of the 01930s and ’40s. During that time, he began using household items and non-musical objects in his compositions, as well as writing for a piano that he modified by placing items like coins and tacks in between its hammers and strings.

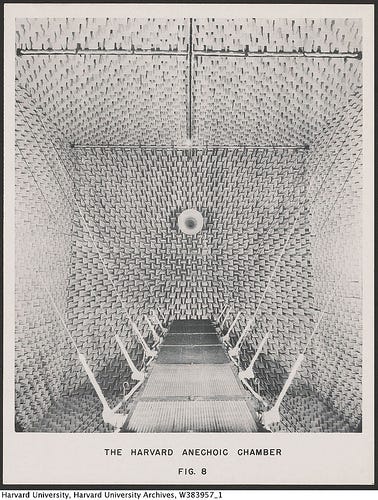

Experimenting with what kind of sounds could be called music led him to his most iconic composition. At Harvard, he was able to access a room specially designed to block out all external sound, an anechoic chamber:

From Rhode Island I went on to Cambridge and in the anechoic chamber at Harvard University heard that silence was not the absence of sound but was the unintended operation of my nervous system and the circulation of my blood. —John Cage

This experience inspired 4’33’’, a composition written in 01952 that instructs its performer to play nothing for four minutes and thirty-three seconds and encourages its listeners to hear the many sounds that make up what would normally be called silence.

Though his most famous, 4’33’’ was but one of many experimental compositions by Cage. Time and rhythm were important to him, and in 01987 he composed a piece for organ that took its name from its tempo. While it would have traditionally been delineated using Italian terms like allegro or andante and more recently in units of Beats Per Measure (BPM), As Slow As Possible leaves quite a bit more open to the performer’s interpretation. Organ²/ASLSP (As SLow aS Possible), as it is more formally known, has been taken on as a challenge by performers over the years, but none have gone to such extreme lengths as a group of organ enthusiasts in Germany.

In 01997, a symposium on organs was held in Trossingen, Germany, and among the discussions was one about Cage’s As Slow As Possible. They took the physical life of an organ to be the main limiting factor of the piece’s slowness and hatched a plan to put on one of the longest concerts ever. The first instrument to be created that could be called an organ, they determined, had been built in 01361, in a church in Halberstadt, Germany. Their performance of As Slow As Possible would be in that same church, on a recreation of the original organ. The piece was scheduled to begin in 02000, 639 years after the organ’s invention. They decided that duration would determine the tempo — that the performance must last as long as the oldest known organ, or until 02640.

The 639 years back to the Faber organ with its 12 tone keyboard was mirrored forward at the millennium change into the minimum of 639 years for the current performance. Halberstadt itself was transformed into a structure, both of time and space, pointing simultaneously backward and forward as is manifested in both directions via the duration set for the performance of the piece. (Harriett Watts, December 6th correspondence)

With the church repaired and the organ rebuilt, weights rest on the keys to play the piece and are moved occasionally as the score progresses. The last note change occurred on October 5, 02013. The next change will not occur until 2020. The performance is supported by an organization that wasn’t officially founded until five years after it had begun: The John Cage Organ Project Arts Association. To help the project, enthusiasts are encouraged to choose a year, between now and 02640, to fund and can have a plaque installed in the church to mark the donation. The Association’s website now dutifully tracks the time and notes that have passed and the ones that are yet to come as well as offering information about visiting the organ and events centered around note shifts.

John Cage himself may or may not have imagined As Slow As Possible to be an experiment in long-term thinking, but his admirers have undertaken a challenging exercise on his behalf. If they are successful, his work will be heard and known in Halberstadt for at least the next 6 centuries.

Jem Finer and Longplayer

Jem Finer’s foray into extremely long-term performance came about very differently from Cage’s. Finer grew up in England and studied not music, but computer science. He was a founding member of punk band The Pogues, and wrote much of the group’s music until they disbanded in 01996.

Around that time, he was approached by Artangel, a British group that commissions unique artworks “which impact upon the way we view our world, our times and ourselves in unusual and enduring ways.” Out of the conversations and collaboration with Artangel came Longplayer, a composition intended from its inception to last 1,000 years:

In the mid 1990s, as the year 2000 approached, I started to wonder about how to make sense of a millennium — that is, how to render as sensible or tangible the great span of one thousand years, not so long in cosmic terms but sufficiently longer than a human lifetime — and how to possibly focus the mind on time as a longer and slower process than the frenetic jump-cut pace of the late 20th Century.

It occurred to me that to make a piece of music exactly 1000 years long not only solved the problem of how to “make” time, but added another dimension to the idea by opening up questions about music and sound, composition and duration. The simple idea that popped into my mind, “write a 1000 year long piece of music,” demanded solutions to an ever expanding range of questions; how to deal with changing cultural perceptions of music, how to listen to music too long to hear completely, where to place it, what technology to base it on, how to make it available to the public… and perhaps most importantly, how to plan for its survival. — Jem Finer

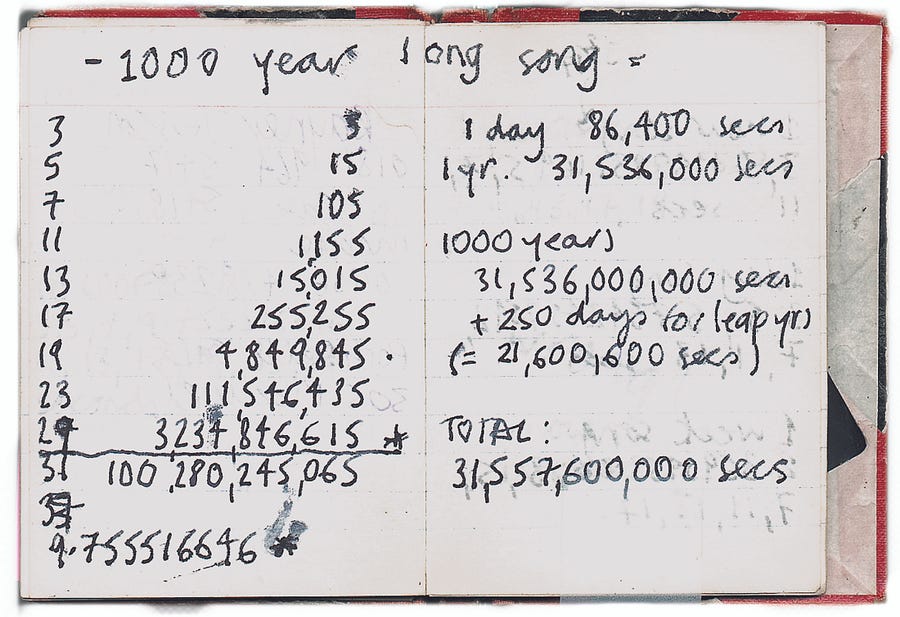

Ten centuries’ worth of music would seem a lot to write, but Finer devised a combinatorial system that would generate the full amount from a more reasonable set of source recordings. Finer played singing bowls for the recordings and then wrote a software algorithm that layers and combines the recordings so they generate a pattern that takes 1,000 years to repeat:

Longplayer is composed in such a way that the character of its music changes from day to day and — though it is beyond the reach of any one person’s experience — from century to century.

It works in a way somewhat akin to a system of planets, which are aligned only once every thousand years, and whose orbits meanwhile move in and out of phase with each other in constantly shifting configurations.

In a similar way, Longplayer is predetermined from beginning to end — its movements are calculable, but are occurring on a scale so vast as to be all but unknowable. — Jem Finer

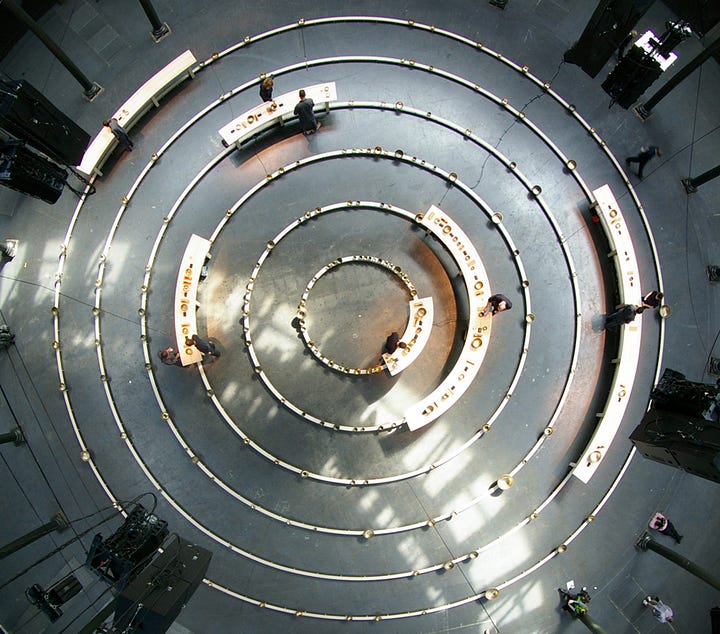

The currently ongoing performance of Longplayer began at midnight on December 31st, 01999. It will continue to play without repetition until December 31st, 02999, at which point it will begin again. It is being performed by a computer and can be heard online or at a number of physical locations around the world, including the lighthouse at Trinity Buoy Wharf in East London, Yorkshire Sculpture Park near Wakefield, Yorkshire, at Kings Place, Kings Cross, London. Beginning on June 7, 02018, a new listening post will launch in Amsterdam in a tower on the roof of the Lloyd Hotel.

On occasion, the digital performance of this piece is accompanied by live performers. In 02010, Long Now helped produce an event in which Jem Finer and others filled in for the computer for a 1,000 minute (that’s 16.6 hours) segment.

Unlike As Slow As Possible, Longplayer has always been explicitly about long-term projects and survival. To sustain funding and continuity through changes in culture and technology, the Longplayer Trust was established. In 02017, a new fund, Buying Time, was launched.

Jem Finer intended from the start to grapple with the long-term in Longplayer. For eighteen years, the piece has resonated online, in listening stations and concert halls. He has worked to ensure it will ring throughout this Millennium and in so doing, to encourage us to consider such a long time-span.

Written by Austin Brown, Danielle Engelman, and Alex Mensing. Edited and updated by Ahmed Kabil.

Learn More

Read a 02011 Washington Post profile of John Cage’s As Slow As Possible performance.

Read a 02009 Guardian profile of Jem Finer’s Longplayer.

In 02017, Longplayer hosted a Longplayer Conversation between naturalist Sir David Attenborough and sound recordist Chris Watson.

Read about the conceptual background of Longplayer.