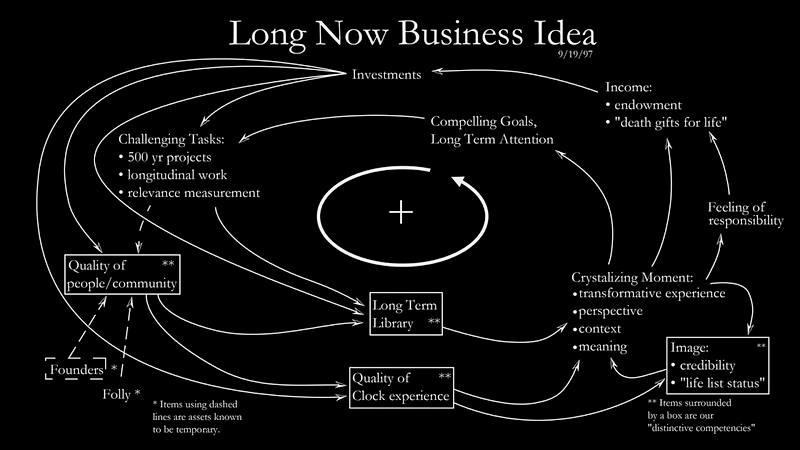

The Long Now Foundation was founded in 01996 with the idea to build a 10,000 year clock — an icon to long-term thinking that might inspire people to engage more deeply with the future. We have been prototyping and designing the Clock since then, and are now in the installation phase of the monument scale version in West Texas.

It was acknowledged at the inception of Long Now that while designing and building a mechanical device to last 10,000 years would involve difficult engineering, designing the institution to last along side it was the truly challenging project. We have human-made artifacts from tens of thousands to even millions of years ago, but there are vanishingly few human organizations and institutions that have lasted longer than even a single millennia. Even more concerning is the trend that organizations are lasting for shorter and shorter lengths of time, even though the challenges such organizations must address — whether they be climate change, education, ecosystem viability — are only increasing in terms of temporal significance.

As we stand at the edge of a generational shift as an organization, it became clear that we needed a generational unit of time — 25 years — to use for our planning. There are four hundred 25 year generations in 10,000 years, and we are just closing the very first one. So if the “Long Now Quarter” is 25 years, and we spent our first quarter building the Clock and our community, it is now time to start planning our second quarter in which we are thinking seriously about how to create a very long-lived organization.

In February, we held a small charrette at The Interval to broaden our thinking about building long-lived institutions. The group consisted of Long Now staff, board members, and outside experts.

Scenario Planning for the Long-term

The event opened with Peter Schwartz, a founding board member of Long Now and author of The Art of the Long View, giving an overview of his work in scenario planning for organizations.

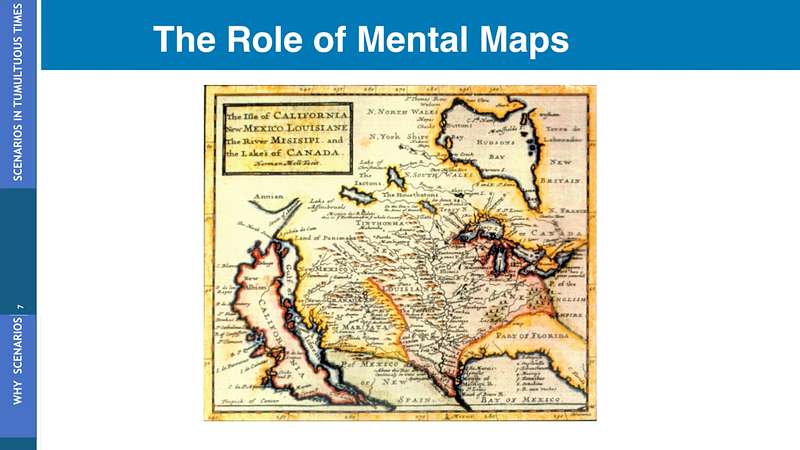

Schwartz discussed how organizations are often limited by mental maps in the choices they make about the future. Effective scenario planning helps organizations build a broader set of mental maps so that they are better prepared for a changing future. The test of a good scenario, Schwartz argued, is not whether or not it is accurate. Rather, it’s about whether or not the leadership of an organization is influenced to make better decisions in light of that scenario.

Intellectual Dark Matter

Following Schwartz, Samo Burja, a researcher specializing in how civilizations function, introduced the idea of intellectual dark matter, which he defines as“knowledge we cannot see publicly, but whose existence we can infer because our institutions would fly apart if the knowledge we see were all there was.”

Burja explored how civilizations have historically lost knowledge, information, and in some cases even the foundations of their entire societies. In so doing, he was able to highlight many areas that any organization aspiring for long-term survival must avoid.

The Data of Long-Lived Institutions

Following Burja, I gave an overview of some of my research into what type of organizations last, what they have in common, and which elements and strategies they developed that have contributed to their survival. Unfortunately, some of the longest-lived organizations, such as the Catholic church or a temple building company in Japan, have some of the least portable lessons for us. Their success is too singular, and the result of highly specific circumstances that will never apply to another organization.

As we delve into the stories of the world’s longest lived organizations more deeply, we are looking for mechanisms that we can borrow and put into practice as cultural institutions, companies, and governments. In so doing, we hope to extend the lifespan of many more organizations so that they are better able to address issues facing humanity that need more than a few years to solve. Imagine if the World Health Organization had been around for a millennia or two, with all their health data intact, how valuable of a resource this would be. It seems that it is our duty to make sure the resources are available for some version of the WHO and its data can last at least that long in to the future.

The Longevity of Nature

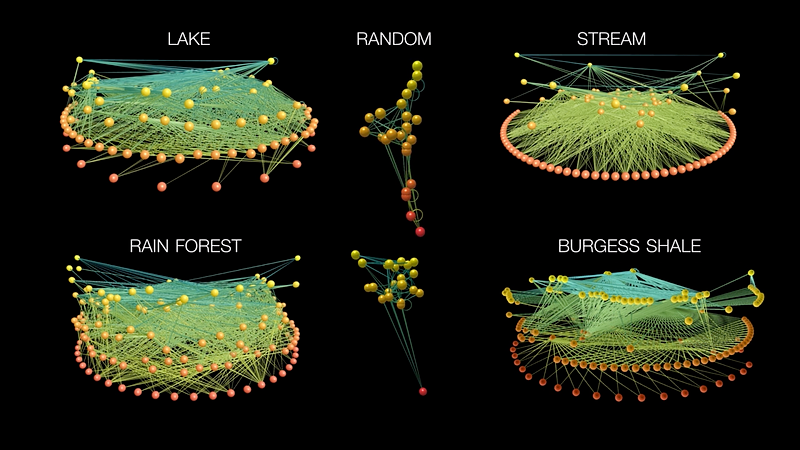

To broaden our thinking about the mechanisms of long-term systemic success, we heard from complexity researcher Dr. Eric Berlow, who has been mapping ecological systems to see how robust or fragile they may be. Berlow’s detailed studies of these complex systems are used to create beautiful and informative visuals that clearly map how dependencies in a system combine to create the whole.

The recurring theme in nature, Berlow said, is that everything is connected, but not equally connected or randomly connected. “The non-randomness in the patterning of the architecture of nature,” Berlow concluded, “is where the library of information about longevity exists.”

Language, Meaning, and Culture

In the afternoon, the director of our own Rosetta Project, Dr. Laura Welcher, a PhD linguist, discussed one of the longest lived human systems — language itself. While language has been with us for a very long time, it is an evolving and changing system. Welcher pointed out the drastic difference between preserving information vs meaning.

Generational Transitions and Governing Systems

The last talk of the day came from one of Long Now’s board members, Katherine Fulton. Fulton emerged as a leading thinker on impact investing and the future of philanthropy, and has worked for many companies and foundations as they transition from one generation to the next.

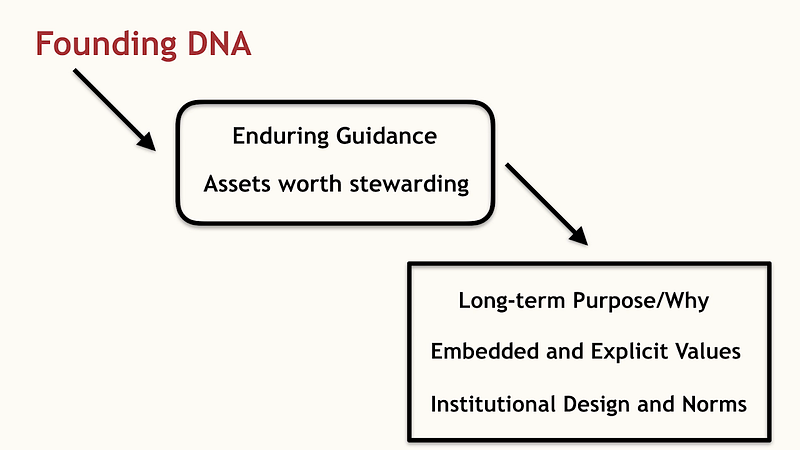

Fulton pointed out that generational change, and how it is handled, is often one of the most critical moments in any organization that hopes to last more than a decade or two. In times of generational change, much of the ability for a successful transition comes from the founding DNA and governing systems that were set up at the organization’s inception.

This is just the beginning of our inquiry into understanding how organizations last. Key questions remain: How do we create best practices for governing systems? How do we develop a culture that is attuned to the nuances of systemic robustness? Fundamentally, this is a systems design question. For a system to last, it needs to have ways of adapting to a changing world, and be able to fail in small ways, and recover from those failures without having the whole system crash. I suspect that as we learn more about specific examples of long-lived organizations, we will hear about several instances in which they almost failed, only to recover and become stronger as a result. As we continue our learning, we hope to create the beginning of a knowledge base that is applicable not only to Long Now, but to any organization aiming to thrive across generations.

We would like to thank all those who participated in the workshop:

- Stewart Brand — President of The Long Now Foundation and founder of the Whole Earth Catalog

- Peter Schwartz — Board Member at Long Now and Senior VP of Strategic Planning at Salesforce

- Katherine Fulton — Board Member at Long Now and former President of the Monitor Institute

- Samo Burja — Researcher at Bismarck Analysis

- Alexander Rose — Executive Director of The Long Now Foundation

- Laura Welcher — Director of Operations and the Long Now Library

- Danica Remy — President of B612 Foundation

- Marty Krasney — Executive Director of the Dalai Lama Fellows

- Eric Berlow — Ecological Network Scientist, Co-founder of Vibrant Data Inc.

- Lawrence Wilkinson — Chairman of Heminge & Condell and Vice Chairman of Common Sense Media

- Abby Smith Rumsey — Writer and Historian

- Jim O’Neill — Managing Director Mithril Capital Management

- Nicholas Paul Brysiewicz — Director of Development at The Long Now Foundation

- Daniel Claussen — Research Fellow at The Long Now Foundation

- James Cham — Partner at Bloomberg Beta

- Frances Winter — Chair of English Department at Massbay Community College

- David Lei — Co-founder of the Chinese American Community Foundation

- Zhan Li — Researcher at the Gottlieb Duttweiler Institute

- Lulie Tanett — Writer

- Frederick Leist — Information Technology Consultant, Medieval Linguistics

- David McConville — President of the Buckminster Fuller Institute

- Erik Davis — Author and Journalist

- Gary Yost — Founder of Wisdom VR, Filmmaker and Software Designer

- Hannu Rajaniemi — Science Fiction Author

- Tim Chang — Partner at Mayfield Fund